When Donald Trump won the US presidential election last November many commentators (us included) thought that his victory would embolden the far-right in Europe by further normalising his radical discourse and policy stances (the “strengthening hypothesis”). But then Trump started implementing overly aggressive policies concerning Europe, e.g. confronting Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy and announcing tariffs on the whole of the EU. As a result, some analysts began to argue the opposite, i.e. that his unpredictability and confrontational approach towards Europe may inadvertently weaken the far-right parties that previously saw him as an ally (the “weakening hypothesis”). Who was right? Data suggests that the answer is… neither.

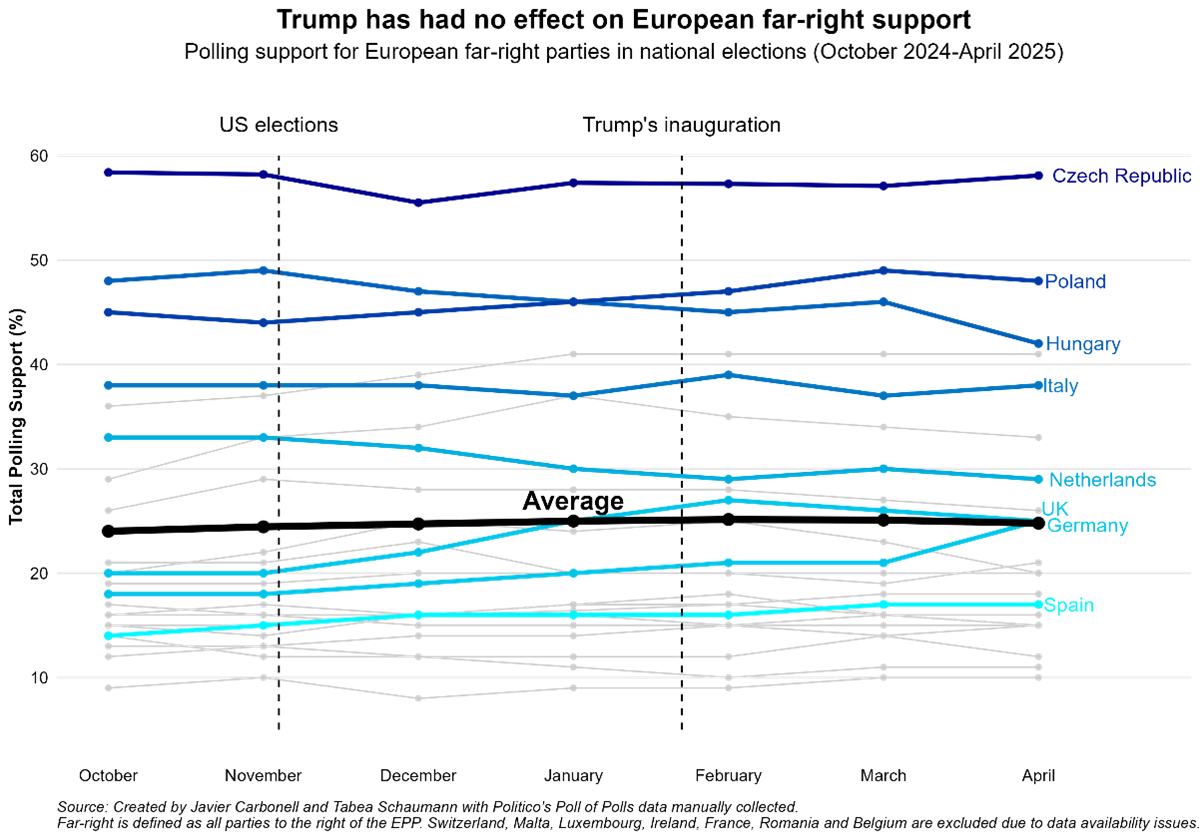

As shown in the graph below, the average support for the far-right in national elections has barely changed over the past six months. Voting intentions for parties that place themselves to the right of the European People’s Party (EPP) has increased slightly in some countries (e.g. Germany and Spain) and decreased somewhat in others (e.g. the Netherlands and Hungary), while the overall European average remained almost unchanged. Moreover, most countries exhibit a stable trend rather than a clear upward or downward movement (e.g. Italy). Additionally, there is no evident impact of key US political events – such as the presidential election or Trump’s inauguration – on voting intentions in Europe. In fact, far-right support in October 2024 closely mirrors that of April 2025. Thus, Trump’s election and subsequent policies appear to have had no clear effect on his European counterparts.

If anything, Trump’s strengthening effects on the far-right seem to have been offset by his weakening effects.

Strengthening effects

Trump has helped to further normalise far-right frames and ideas. By shifting the Overton Window – the range of acceptable political discourse – Trump makes it easier for European far-right leaders to adopt more radical positions on immigration, economic nationalism and scepticism toward multilateral institutions without facing immediate backlash. Many far-right leaders have spoken about the “turning point” Trump’s elections implies for them and gathered in February 2025 in Madrid at the "Make Europe Great Again" Conference. Their ideological alignment with the new US administration was illustrated by J.D. Vance's speech at the Munich Security Conference in which he argued that the biggest threat is not Russia or China but the very pillars of European liberal democracies – the usual and common ‘enemy’ of the far right.

Trump’s presidency has also elevated the role of far-right leaders in diplomatic affairs. Far-right leaders can position themselves as intermediaries between the US and European governments, circumventing EU institutions and blocking EU policies. For instance, Orbán’s unilateral ‘peace mission’ to Moscow and Beijing in July 2024, announcing Trump’s readiness to act “immediately” as a peace broker between Ukraine and Russia after taking office, bypassed the bloc’s efforts to sustain unequivocal support for Ukraine. Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni's recent visit to Washington to negotiate EU tariffs with President Trump, highlighted her intermediary role between the US and the EU. However, the solo nature of her trip raised concerns about the strength of European unity.

Weakening effects

Yet Trump’s “America First” approach and its impact on European security (taking a soft line on Russia) and the economy (imposing sweeping tariffs) did not bode well for the far right. As Ben Ansell argues, Trump can make far-right European parties appear to be unpatriotic and aligned with a “foreign enemy.” For example, Spanish Socialist Minister Óscar Puente recently accused far-right Vox leader Santiago Abascal of being a “vendepatrias” (a sellout to his nation) because Abascal did not criticise Trump’s tariffs.

Fears of war have prompted Europeans to ‘rally around the flag’, essentially strengthening mainstream parties rather than the populist movements that had hoped to benefit from Trump’s support. This is reflected in record-high EU membership approval rates among EU citizens, a prioritisation of defence and security and a negative opinion of Trump. A recent survey by Le Grand Continent and Cluster 17 on major EU countries found that more than half of the respondents view Trump as an “enemy of Europe”, with only a small minority – 8% in Germany, 7% in Spain and 6% in France – seeing him as a “friend”. Similarly, a YouGov poll showed that since Trump’s re-election, favourable views of the US have sharply declined across Western Europe, dropping from 48% to just 20% in Denmark, 49% to 29% in Sweden, 52% to 32% in Germany, and 50% to 34% in France.

Trump’s policies are also felt by far-right voters. In the UK, a YouGov poll reveals that following the Trump-Zelenskyy meeting on 28 February, disapproval rates of Trump among the British respondents increased from 73% to 80%. Strikingly, this trend was most prevalent among far-right Reform UK voters, increasing from 28% mid-February to 53% only two weeks later.

Moreover, the February Trump-Zelenskyy clash did not only strain relations with Trump but exposed significant fractures within the European far right. Several leaders distanced themselves from Trump’s statements, such as Dutch far-right leader Geert Wilders, who reaffirmed his support for Ukraine “with conviction”, adding that the meeting was “not necessarily the best way to end the war”. Similarly, Reform UK leader Nigel Farage described the encounter as “regrettable and will make Putin feel like the winner”. Marine Le Pen, leader of the National Rally in the French National Assembly, condemned Trump’s decision to halt aid to the country as “brutal”. In contrast, Kremlin-sympathising leaders defended Trump’s approach, including Alternative for Germany’s Alice Weidel and Tino Chrupalla, Lega’s Matteo Salvini in Italy, as well as Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán.

Furthermore, Trump's imposition of the now halted 20% tariffs on European imports, further negatively impacted relations with European far-right leaders, whose political bases are directly affected by these measures. In France, the cognac industry, which heavily relies on the US market for half of its sales, already faces severe challenges. Producers are experiencing drastic sales decline, leading to vineyard uprooting and workforce reductions. Similarly, Italy's wine sector is anticipating a potential 25-35% drop in US consumption. This decline would threaten approximately €323 million in annual revenue, jeopardising numerous jobs within the industry. These economic hardships directly affect the working-class supporters of far-right parties, like National Rally and Lega, who have traditionally championed national industries and workers' rights. If these voters see their parties aligning with the person responsible for their economic hardship they could turn away from the far right.

Overall, the far right’s polling stability and the contradictory effects of Trump suggest that far-right support in Europe is largely independent of the new US president. He has not had the substantial impact predicted by either the “strengthening” or “weakening” hypotheses. Variations in support for far-right parties are more likely explained by domestic factors – such as participation in government, media controversies, economic hardship, and their interaction with the European Union – rather than by Trump. The overall lesson for EU leaders is clear: the far-right problem is home-grown and therefore requires home-grown solutions.

Tabea Schaumann is a Programme Assistant at the European Policy Centre.

Javier Carbonell is a Policy Analyst in the European Politics and Institutions Programme at the European Policy Centre.

The support the European Policy Center receives for its ongoing operations, or specifically for its publications, does not constitute an endorsement of their contents, which reflect the views of the authors only. Supporters and partners cannot be held responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.